Hey there, design darlings!

Our world is full of creativity, constantly reshaped by dynamic design movements that have spiced up our visual world. So, buckle up and let’s embark on a fascinating journey through the world of design movements, exploring their essence, impact, and enduring influence on our lives.

What’s All the Fuss About “Design Movements”?

At its heart, a design movement is a collective, often groundbreaking response to the cultural, social, and technological zeitgeist. It’s an era that can be defined by a shared design ethos, a distinct aesthetic language, and a group of trailblazing designers who create a whole new design language. These movements often span across creative realms, encompassing architecture, interior design, graphic arts, fashion, and more.

Whilst design movements are usually defined by a certain time frame, movements can overlap and influence each other. The closer we move to the current day, the more defined the movement period is.

The Birth of a Movement

Design movements are born out of a desire to break free from existing norms and to respond to the prevailing societal context. For example:

- The Arts and Crafts Movement (late 19th century): This movement was a reaction to the industrialization of the Victorian era, championing the beauty of craftsmanship and the handmade.

- The Bauhaus Movement (1919-1933): Post-WWI, the Bauhaus emerged to merge art and industry, advocating functionalism, and the reduction of ornamentation.

Design movements push the boundaries, encouraging new ideas and perspectives.

Key Elements of a Movement

Every design movement has its own flair:

- Aesthetic Principles: Each movement has its unique visual style, like Art Deco’s geometric patterns and Art Nouveau’s organic forms.

- Philosophical Foundations: Movements are often underpinned by a set of beliefs. Modernism, for instance, was driven by the idea that design should embody the spirit of the age.

- Pioneering Figures: Iconic designers and artists often lead these movements. William Morris was at the forefront of the Arts and Crafts movement, while Walter Gropius was a key figure in Bauhaus.

Societal Context

Design movements are deeply intertwined with the social, political, and technological climate of their time. They often reflect or rebel against the dominant cultural norms. For instance, the counterculture movements of the 1960’s inspired design elements that embraced non-conformity.

Technological advances like the printing press, photography, and the internet have profoundly influenced how design is created and shared. In addition, social issues like feminism and civil rights have profoundly impacted design, fostering more inclusive and diverse expressions.

Why Do Design Movements Matter?

Design movements are historical markers of our cultural evolution. They matter because they reflect society, mirroring society’s values, concerns, and aspirations. The design of a period is a window into the collective consciousness. Movements encourage new thinking and innovation. They challenge the status quo and inspire fresh perspectives.

The impact of these movements extends beyond their time. Their principles continue to shape contemporary design, as seen in the lasting influence of mid-century modernism.

Design Movements

Let’s have a look at some standout movements:

Gothic (12th – 16th century): The Dawn of Splendor

The gothic period marked a significant departure from the Romanesque style, ushering in an era of towering cathedrals and intricate ornamentation. Originating in 12th-century France, Gothic architecture quickly spread across Europe. Its hallmark features include pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses, all contributing to the ethereal and heaven-reaching designs of buildings like the Notre-Dame de Paris.

In England, the Gothic style evolved into what we call the English Gothic, with notable examples like the Canterbury Cathedral. This variant retained the essential Gothic elements but often included more elaborate stonework and larger windows, culminating in the Perpendicular Gothic style noted for its strong vertical lines.

While the Gothic period is primarily known for its architectural wonders, its influence on interior design cannot be overlooked. The Gothic Revival (mid-19th century) in England was led by designers like Augustus Pugin, who emphasized authenticity in the use of medieval motifs and heralded a return to craftsmanship. This was evident in the Houses of Parliament’s interiors, where Gothic Revival elements were incorporated into everything from wallpapers to furniture.

Renaissance (14th – 17th century): Rebirth of Classicism

The Renaissance, a word literally meaning ‘rebirth’, was exactly that for European art and design. Beginning in 15th-century Italy, this movement sought to resurrect the art and philosophy of ancient Greece and Rome. It emphasized symmetry, proportion, and geometry – hallmarks of classical design, and contrasting sharply with the Gothic’s complex verticality. The Renaissance period, celebrated for reviving classical antiquity’s art and philosophy, also significantly influenced interior design. The interiors were marked by a rich colour palette with often hefty and ornately decorated furniture.

Renaissance design manifested in various forms across Europe. In England, the Elizabethan style, named after Queen Elizabeth I, embodied the English Renaissance. This style was less about reviving classical antiquity and more about meshing Gothic elements with new Renaissance influences, resulting in stately homes with intricate facades and elaborate interiors. Elizabethan style can be characterized by heavy oak furniture, elaborate carvings, and rich tapestries. The Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire is a classic example, where these elements come together in a distinctly English interpretation of Renaissance luxury.

Baroque (17th – 18th century): Extravagance and Grandeur

Baroque, starting in the early 17th century in Italy, was all about drama, tension, and grandeur. This was the era of opulent palaces and grandiose churches, characterized by ornate details, bold colours, and dynamic forms. The Baroque style was a sensory feast, aiming to awe and inspire through its sheer extravagance. The rooms were large, with high ceilings, and richly decorated with bold colours, large paintings, and lavish tapestries. Furniture was often gilded and ornate, complementing the dramatic architectural elements.

In England, the Baroque movement was less pronounced but found expression in architecture through works like the Blenheim Palace. English Baroque was a tempered version of its continental counterpart, focusing more on bold contrasts and less on overwhelming ornamentation. Hampton Court Palace exemplifies the English Baroque interior, with its sumptuous fabrics, ornate ceilings, and intricate woodwork.

Rococo (18th century): Playful and Ornate

Emerging as a reaction against the grandiose and religious Baroque, Rococo was all about lightness, elegance, and playful ornamentation. Originating in early 18th-century France, this style was characterized by pastel colours, sinuous curves, and asymmetrical designs. Rococo was less about awe and more about enjoyment, evidence in the whimsical and intimate interiors of the time.

In England, the Rococo style was embodied in interior design and decorative arts rather than architecture. English Rococo was more restrained than its French counterpart, focusing on intricate craftsmanship and elegant detailing. The Rococo style is evident in the interiors of homes like the Spencer House in London, where the decorative arts, including mirrors, ornamental plasterwork, and furniture, reflected the Rococo’s light and playful spirit.

Neoclassicism (late 18th century): Return to Simplicity

In the late 18th century, as a response to the excesses of Baroque and Rococo, Neoclassicism emerged, drawing inspiration from the classical art and culture of Ancient Greece and Rome. This movement emphasized clarity, simplicity, and symmetry, reflected in the architectural styles of the time. Interiors were characterized by clean lines, subdued colours, and the use of motifs like laurels, urns, and columns. Furniture was elegant and less ornate, often made from mahogany and decorated with classical motifs.

In England, Neoclassicism was exemplified in the Georgian design movement by the works of designers like Robert Adam, whose work at Syon House and Kenwood House in London is characterized by light, elegant rooms with classical motifs and restrained ornamentation. Architects brough a distinct English interpretation to Neoclassicism, often incorporating innovative structural techniques and interior designs that were simultaneously classical and modern.

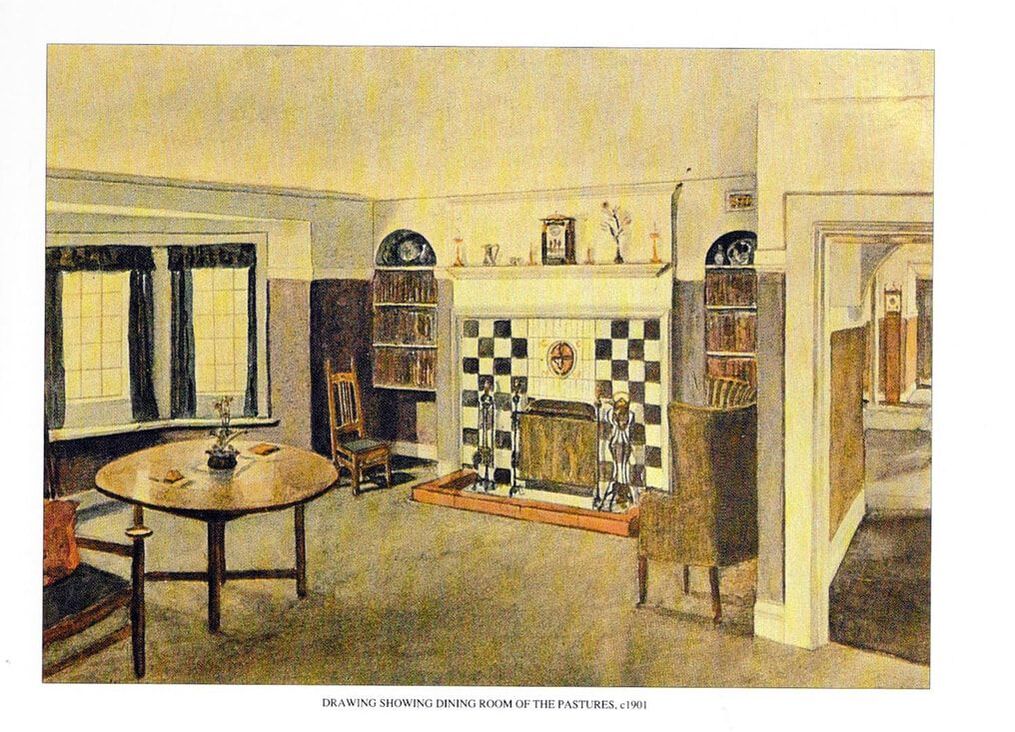

Arts and Crafts (Late 19th century): A Return to Handmade Quality

The Arts and Crafts movement, originating in England in the late Victorian period, was a response to the industrialisation of the era. Promoted by figures like William Morris, this movement sought to revive traditional craftsmanship and elevate the status of decorative arts. It emphasized simple forms, natural materials, and motifs inspired by nature and medieval styles. Interiors features handcrafted furniture, often made of oak, with simple, straight lines and minimal ornamentation. There was a strong emphasis on textiles, with handwoven tapestries and fabrics featuring natural motifs like flowers and birds.

In England, the Arts and Crafts style was exemplified by the homes designed by Charles Voysey, where the integration of architecture, furniture and decorative arts created a harmonious and unpretentious living space.

This movement had a significant impact across Europe, inspiring similar movements like the Art Nouveau, which emphasized flowing lines and organic forms.

Art Nouveau (late 19th to early 20th century): Nature and Flowing Lines

Art Nouveau, flourishing between 1890 and 1910, brought a distinct aesthetic characterized by flowing lines, natural forms, and an emphasis on decorative arts. This movement represented a departure from the historical revivals of previous styles, seeking instead to create a new, modern style. The style often featured floral motifs, stained glass, and curvilinear forms. Furniture was designed to be both functional and beautiful, with an organic feel.

In England, Art Nouveau was less prevalent but found expression in the works of artists like Aubrey Beardsley and Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who incorporated Art Nouveau’s distinctive style into their designs.

Art Deco (1920’s – 1940’s): Glamour and Symmetry

Following the organic curves of Art Nouveau, Art Deco emerged in the 1920’s as a symbol of luxury, glamour, and technological progress. Characterized by geometric shapes, bold colours, and lavish ornamentation, it reflected the exuberance of the Roaring Twenties and the Machine Age. And the interiors were no different, with bold geometric shapes, rich colours, and luxurious materials like chrome, glass, and mirrored surfaced. Notable European examples include the Chrysler Building in New York and the Palais de Chaillot in Paris.

In England, Art Deco was synonymous with elegance and modernity. London’s underground stations and the Odeon cinemas are quintessential examples, showcasing streamlined forms and the use of new materials like chrome and stainless steel. The Art Deco style was epitomized by interiors such as those in the Claridge’s Hotel in London, which combined luxury and modernity.

Modernism (early to mid-20th century): Functionality and Simplicity

Modernism, emerging in the early 20th century, represented a radical break from the past. This movement sought to embrace the possibilities of new materials and technologies, stripping away ornamentation to focus on functionality and simplicity. Furniture was often sleek, made from new materials, and designed to be mass-produced.

In England, Modernism took a unique form, often blending traditional materials with modern design principles. This is evident in buildings like the Highpoint I in London, which combines modernist ideals with a sensitivity to the English architectural context, and the Isokon Building in London, with its minimalist interiors and furniture designed by Marcel Breuer, are notable examples of English Modernism.

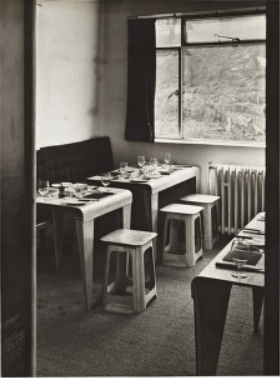

Bauhaus (1919-1933): Blending Art and Functionality

Originating in Germany, the Bauhaus movement profoundly influenced modernist architecture and design. Founded by Walter Gropius, Bauhaus embraced the philosophy of “form follows function,” emphasizing simplicity, rationality, and the integration of art, craft, and technology. This movement left a lasting mark on everything from furniture design to architecture. Bauhaus interiors were minimalist, with an emphasis on clean lines and the use of industrial materials like steel and glass.

While the Bauhaus movement itself was short-lived, its principles spread across Europe, including England, where it influenced the Modernist architecture movement, emphasizing functionalism and a lack of ornamentation.

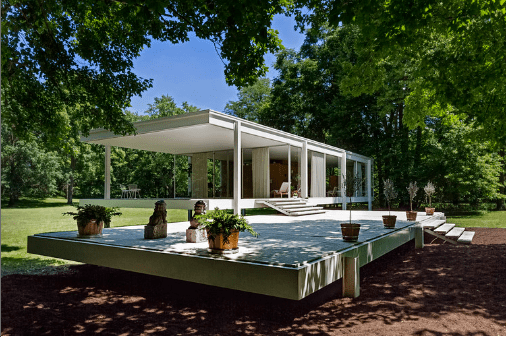

Mid-Century Modern (1930’s – 1960’s): Organic and Sleek

Mid-Century Modern, spanning from the 1930’s to the 1960’s, is characterized by clean lines, organic forms, and a seamless flow between indoor and outdoor spaces. This movement reflected post-war optimism and the desire for modern, uncluttered living. Furniture designs were often sleek yet comfortable, utilizing new materials and manufacturing methods. The style emphasized functionality but also brought a sense of warmth and organic aesthetics to the interiors.

In England and across Europe, this style manifested in furniture design and architecture, with designers like Arne Jacobsen and Eero Saarinen becoming household names. The use of new materials like plastic and plywood allowed for innovative, often sculptural, furniture designs.

Postmodernism (late 20th century): Irony and Eclecticism

Emerging in the late 20th century, Postmodernism marked a departure from the strict functionalism of Modernism. It embraced complexity, contradiction, and irony, often referencing and mixing different historical styles. This movement is known for its eclectic, colourful, and sometimes whimsical aesthetic.

In Europe, Postmodernism found expression in projects like the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart by James Stirling, which combined classical architecture with bold, contemporary elements. The postmodern style was exemplified in interiors like those designed by Ettore Sottsass and the Memphis Group, known for their vibrant, unconventional furniture and décor.

Minimalism (Late 20th century – present): Less is More

Minimalism, often summarized by Mies van der Rohe’s motto “less is more,” emphasizes simplicity, clean lines, and a monochromatic palette. It’s a response to the excesses of consumerism, advocating for a lifestyle that values quality over quantity.

This design ethos is evident in contemporary European architecture and interior design, where the focus is on space, light, and simple forms. Minimalism isn’t just a style; it’s a philosophy that continues to influence various aspects of design and lifestyle. Contemporary minimalist interiors often feature a blend of natural materials, simple forms, and a connection to the surrounding environment.

Contemporary (21st century): A Melting Pot of Styles

Today’s design landscape in Europe is incredibly diverse, reflecting a blend of historical influences and cutting-edge innovation. Contemporary design often incorporates sustainable materials and practices, acknowledging the growing importance of environmental stewardship. It’s not uncommon to see a fusion of styles – like the warmth of Scandinavian design mingling with the minimalism of Modernism.

In England and across Europe, contemporary design continues to evolve, driven by technological advancements, global influences, and a growing awareness of social and environmental issues. This era is less about defining a singular style and more about adapting and innovating to meet the changing needs and values of society.

And that my friends, is a glimpse into design movements – the pulsating heart of design history. Today, we’ve focused on British and European design movements, but there have been design movements in all corners of the globe, reflecting the rich cultural, spiritual, and historical context of their regions.

Until next time, keep exploring and appreciating the beauty in every corner!

JG x

Resources

- Architectural Digest. (2018). Walter Gropius: Founder and Director of the Bauhaus [Online]. Available at: https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/walter-gropius-bauhaus-100-founder-director-architecture-design (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Architectural Digest. (n.d.). Eero Saarinen’s 1948 Womb Chair Brought Midcentury Modernism to the American Mainstream [Online]. Available at: https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/eero-saarinens-1948-womb-chair-brought-midcentury-modernism-to-the-american-mainstream (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- ArchDaily. (n.d.). Happy 127th Birthday, Mies van der Rohe [Online]. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/350573/happy-127th-birthday-mies-van-der-rohe (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Breuer in Syracuse. (n.d.). Project Details [Online]. Available at: https://breuer.syr.edu/project.php?id=318 (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Britannica. (2024). Notre-Dame de Paris [Online]. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Notre-Dame-de-Paris (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Charles Voysey. (n.d.). History [Online]. Available at: https://www.charlesvoysey.com/history.html (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Claridge’s. (n.d.). Design Features [Online]. Available at: https://www.claridges.co.uk/about-the-hotel/design-features/ (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Country Life. (2020). The Great Hall at Hampton Court [Online]. Available at: https://www.countrylife.co.uk/architecture/the-great-hall-at-hampton-court-the-building-that-brings-the-visitor-closer-to-the-world-of-henry-viii-than-any-other-219593 (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Curbed New York. (n.d.). NYC Art Deco Architecture Map [Online]. Available at: https://ny.curbed.com/maps/nyc-art-deco-architecture-map (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Deezeen. (2018). Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Masterwork [Online]. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2018/06/05/glasgow-school-of-art-charles-rennie-mackintosh-masterwork-150-anniversary/ (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Deezeen. (2020). CFA Voysey: Winsford Cottage Hospital, Devon [Online]. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2020/02/13/cfa-voysey-winsford-cottage-hospital-devon-benjamin-beauchamp/ (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Deezeen. (2021). Ten Mid-Century Modern Interiors [Online]. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2021/09/12/ten-mid-century-modern-interiors-lookbook/ (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Deezeen. (n.d.). Guide to Postmodern Architecture & Design [Online]. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2015/07/23/guide-to-postmodern-architecture-design-glenn-adamson/ (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Doe & Hope. (n.d.). Periods & Styles [Online]. Available at: https://www.doeandhope.com/pages/periods-styles (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Ettore Sottsass Instagram Account (2016, January 15). [Instagram Photo] [Online]. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BAsm3R3iY3z/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=ae80d6e3-c06c-4f32-888c-5af2007e06ee (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Hampton Court Palace. (n.d.). The Story of Hampton Court Palace [Online]. Available at: https://www.hrp.org.uk/hampton-court-palace/history-and-stories/the-story-of-hampton-court-palace/#gs.3p8fpm (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Historic England. (n.d.). [Photograph of Item DP348873] [Online]. Available at: https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/photos/item/DP348873 (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- House & Garden. (2018). Blenheim Palace: History [Online]. Available at: https://www.houseandgarden.co.uk/article/blenheim-palace-history (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Museum Crush. (n.d.). Britain’s Best Places to See: Arts and Crafts Houses and Collections [Online]. Available at: https://museumcrush.org/britains-best-places-to-see-arts-and-crafts-houses-and-collections/ (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- National Trust. (n.d.). History of Hardwick Hall [Online]. Available at: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/peak-district-derbyshire/hardwick/history-of-hardwick-hall (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Parliament UK. (2022). The Palace of Westminster: New Gothic Vision [Online]. Available at: https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/building/palace/architecture/palacestructure/new-gothic-vision/ (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Spencer House. (2021). State Rooms: Painted Room [Online]. Available at: https://www.spencerhouse.co.uk/state-rooms/painted-room (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Syon Park. (n.d.). About Syon House: Long Gallery [Online]. Available at: https://www.syonpark.co.uk/explore/about-syon-house/long-gallery (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- The Collector. (2022). Middle Ages Gothic Revival Buildings [Online]. Available at: https://www.thecollector.com/middle-ages-gothic-revival-buildings/ (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- The English Home. (n.d.). Robert Adam Interiors at Syon House [Online]. Available at: https://www.theenglishhome.co.uk/robert-adam-interiors-at-syon-house/ (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Unique Venues of London. (n.d.). Beautiful Rooms: Palm Room, Spencer House [Online]. Available at: https://www.uniquevenuesoflondon.co.uk/news/beautiful-rooms-palm-room-spencer-house (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- V&A Museum. (n.d.). Robert Adam: Neoclassical Architect and Designer [Online]. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/robert-adam-neoclassical-architect-and-designer (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

Leave a comment